Building a Bittorrent Client

Jun 30, 2022

This post is for those who are interested in the internal details of the BitTorrent protocol.

This post contains all that I’ve learnt about building a BitTorrent Client with C. It’s not a replacement for the BitTorrent Protocol spec. You can find the official spec here though this is not as detailed and thorough as the unofficial spec. I advise you to read both of them for a more comprehensive understanding of the protocol.

This post does not cover working with trackerless torrents using peer exchange and Distributed Hash Table protocol. It only covers the original protocol, which must involve a tracker.

The client I built mainly implements the client side of the protocol and some of the server-side. This means that it can share files if a peer requests for a file but it doesn’t listen for a connection. The only way a peer can communicate with this client is if this client initiates the connection.

You can find the source code of my client on Github.

I’ll start this post by giving an overview of the Bittorrent protocol before going into details.

Overview Of The BitTorrent Protocol

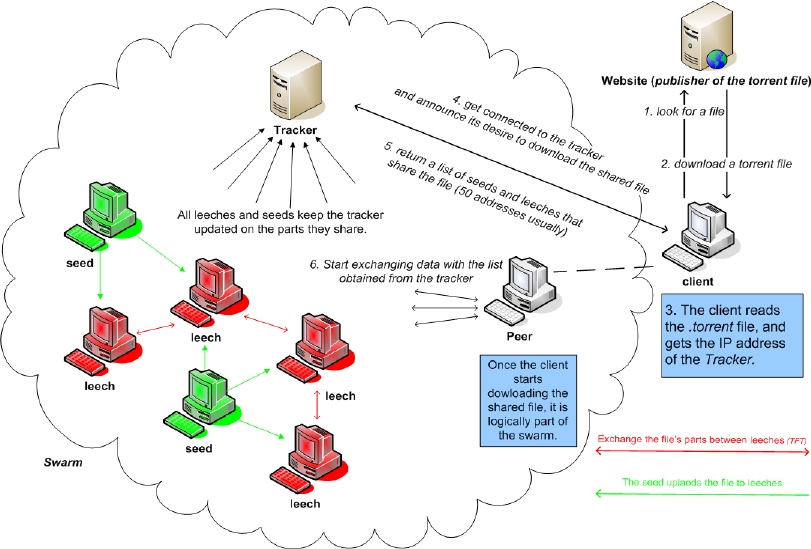

Overview of the Protocol, from Topology Aware Worm Propagation in BitTorrent : Modeling and Analysis by Sinan, Abdelmadjid, and Yacine (2008)

The BitTorrent protocol is a peer-to-peer protocol used for distributing files. This means that a peer can act as a client and a server when sharing a file. There is no central server that all clients connect to download the files. In BitTorrent land, all clients can be servers while all servers are clients.

Let’s say you want to download David Copperfield by Charles Dickens using the BitTorrent protocol. The steps will be:

- You download a torrent file for David Copperfield with your web browser. This torrent file contains some info containing metadata about the book. Some metadata will be the file name and size and may include the file hash for verification purposes. The torrent file will also contain BitTorrent-specific info like the trackers, hashes of the file(s) pieces, and more. Once these are parsed, connection(s) to the tracker(s) is/are initiated.

- The tracker is a server with a record of the IP address and ports of all the peers currently downloading and uploading the file. We connect to the tracker to get a list of peers that are sharing and receiving the file at the time. Once this is done, your device IP address and port are added to this record for the benefit of future peers, but only for a limited time.

BitTorrent is indeed a peer-to-peer protocol, but it has a measure of centralization. BitTorrent now supports true decentralization using DHT, but this won’t be covered here.

Side note. I have noticed that most working decentralized protocols usually incorporate a centralized method for locating other devices before switching to the main protocol for communication similar to the way the internet all uses the 13 root name server addresses for DNS lookup before the main communication starts. - A peer is a device like yours which makes you a peer. There are two types of peers though they aren’t mutually exclusive. The peer who downloads is a leecher, while the peer who uploads is a seeder. A peer can be both a leecher and a seeder. We download pieces of the file from the seeders. A piece is a segment of the file. The file’s pieces are verified and inserted into the file in their correct position. Once all the file’s pieces have been received, the download is complete. If you remain in the network, you stop being a leecher and fully become a seeder.

The protocol performs better when there are more seeders so mechanisms are in place to encourage more seeder-like behavior. I won’t cover these mechanisms. The client I built encourages leeching, so your download speed could be slower than if you use the popular BitTorrent clients.

The Torrent File - technical details

A torrent file is a giant dictionary that contains information on how to download the file. This dictionary is encoded using the bencode format.

The bencode encoding transforms dictionaries, lists, strings, and integers into a giant string. Each data type has its format. For example, the torrent file starts with ’d’ denoting that it’s a dictionary. More details about the bencode format are here and here. Note that dictionaries can contain dictionaries too.

Some of the important keys in the torrent dictionary are listed below:

- announce: This contains the url of a single tracker.

- announce-list: This contains a list of tracker urls.

- info: This is a dictionary that contains file-related details. A hash of the bencoded value of this key (including the d and e) is used by both the trackers and peers to identify the torrent file. Some of the details are:

- pieces: A long binary string consisting of the concatenation of the SHA-1 hash of each piece. Each hash is 20 bytes long, so this makes the length of this string a multiple of 20. We can divide this string length by 20 to get the exact number of pieces to download.

- piece length: the size of each piece in bytes. The size of the last piece might not be as large as this value.

- name: The name of the file/directory to download.

- files: This key only appears when more than one file is downloaded. It’s a dictionary that contains the path and length of each file.

- length: This key only appears directly under the info dictionary when only one file is downloaded. It contains the size of the file in bytes. The value of this gives the accurate file size. When more than one file is downloaded, this key appears under the files key defined above. In this case, a sum of these values gives the total size of the files. The file’s size must be accurately calculated because this helps to correctly infer the last piece’s size. The modulo function can calculate the final piece’s size if the total file size is not divisible by the piece length.

Note that these aren’t all the keys in the torrent file. You can read about more torrent keys and details here.

Communication to the urls extracted from the announce and (maybe) announce-list elements are made to get the peers.

Tracker - communication flow

Communication with the tracker is necessary to get the peers. The trackers can be communicated with by either the UDP or HTTP/HTTPS protocol based on the url scheme. UDP is used for communication with trackers whose urls begin with udp://, while HTTP/HTTPS is used for communication with trackers whose urls start with http:// or https://.

Some of the trackers may produce an error on connection, so getting an error from them doesn’t mean that your protocol implementation is wrong. The error could be caused by a myriad of reasons that are beyond your control. Connecting to more trackers increases your chances of getting peers.

Previously, it was http(s) that was the only communication protocol, but because of the demand on trackers by peers and the overhead introduced by the http(s) protocol, udp was introduced. Both protocols will be covered below.

HTTP(s) Protocol

We won’t cover https here since its only difference from http is that it uses certificates.

A GET request is sent to the tracker where the url is either the announce value or one of the announce-list values. I wrote a simple implementation of this using the sockets library, but you’re free to use any http library of your choice when building your client. Some values are added as parameters to the url. Parameters that need to be encoded have to be encoded using the percent-encoded method. Some of the more important parameters are:

info_hash: This is the urlencoded SHA-1 hash of the info key value in the bencoded torrent dictionary. It is 20 bytes in length. The info key value must include the d and e characters used to delimit the start and end of the dictionary. The hash has to be correct because the tracker uses it to determine the torrent file. If this is incorrect, the tracker will either produce an error or give you a different set of peers. The hash is a binary string and therefore has to be urlencoded.

peer_id: This is a unique id your client generates to identify your device. The length has to be exactly 20 characters long. The characters can even be a binary. Different BitTorrent clients have different conventions for generating peer_id. This parameter value should be urlencoded.

port: The port on which your client is listening. It is typically set to between 6881-6889. If your device is behind a NAT, you might need to use TURN/STUN methods to determine what your port is in the NAT before setting this parameter. If you choose to be solely a leecher, you can set this to 0.

ip: The ip address of your client. If you choose to be solely a leecher, you can set this to 0. It is optional because most trackers ignore this as they can determine this from the ip address your HTTP request is coming on.

compact: This determines the format of the peer string in the tracker’s response. Setting this to 1 ensures that the peers’ list is formatted as a string with each peer being 6 bytes long, meaning that the total string length is a multiple of 6. The ip address and port of a peer are 4 bytes and 2 bytes long respectively. This is surprising because we know that ipv4 addresses in dotted format are a minimum of 7 bytes long (0.0.0.0). Well, they can also be formatted as a decimal number (big-endian notation). The number formatted version of the ipv4 is 4 bytes. The port is 2 bytes because every port can be represented using two 8-bit characters since the range is 0-65535. Setting this parameter to 0 ensures the peers’ list is formatted as a bencoded dictionary. Many trackers prefer requests with this parameter set to 1 to save bandwidth.

Here’s an hypothetical request for a tracker whose url is http://opentracker.bittorrent.com/announce:7456

/GET /announce?info_hash=%124Vx%9A%BC%DE%F1%23Eg%89%AB%CD%EF%124Vx%9A&peer_id=-BT0001-948911116432&port=6889&uploaded=0&downloaded=0&left=489033&compact=1&event=started HTTP/1.1

Host: opentracker.bittorrent.com:7456

If the info hash is correct and the tracker has some peers connected to it, the response will be in a bencoded dictionary format. Some of the keys in the dictionary are:

- interval: The time in seconds that the client should wait before sending regular requests to the tracker. The purpose of this interval is for the client to update their peer list. When downloading the file, there is a high likelihood that the number of peers the client is downloading from will reduce due to peers disconnecting (it’s also possible that the number of peers can drop down to 0 thus ending the download). Download speed will be affected as there is a positive correlation between the number of peers and the download speed. The way to prevent this is for the client to get a new peers list from the tracker at regular intervals. Trackers send this value to prevent clients from sending requests too frequently.

- complete: Number of peers with the entire file(s), also known as seeders.

- incomplete: Number of peers with the incomplete file(s), also known as leechers.

- peers: This contains a list of peers along with their peer id (if compact is set to 0), ip address (dotted if compact is set to 0 or decimal if set to 1), and port. They will be in a list of dictionary format if compact is set to 0 or just a binary string if compact is set to 1.

Here’s an hypothetical reply for the request sent above

d8:completei1e10:downloadedi0e10:incompletei1e8:intervali2988e12:min intervali1494e5:peers12:6@]-N+Nd-6%À

The peers in the reply translate to 54.64.93.45:20011 and 78.100.45.54:9664.

You can read the spec for more information about the tracker HTTP protocol.

UDP Protocol

Due to the overhead introduced by the http protocol, a udp version of the protocol was introduced. Unlike the text-based http protocol, this is binary-based. Because of this, numbers sent to and received from the trackers have to be in network byte order notation referred to as big-endian. Some devices are little-endian (Intel x86 machines) while some are big-endian (Sparc devices). Functions that convert between endianness should be used when communicating with the trackers. In C, htonl, htons, ntohl, and ntohs functions are used. In Python and PHP, the pack and unpack functions are used.

The udp protocol is unreliable, so a retry with timeout flow needs to be implemented.

Unlike the http protocol, which only involves one request-response cycle, the udp protocol involves two cycles. This is to avoid UDP spoofing. The first of these two is called the connect cycle, while the second is called the announce cycle. Both will be covered in this subsection.

The connect cycle is used to get the connection id which will be used in the announce cycle. The connection id is a time-limited value that is required in the announce request. This value is used by the tracker to ensure that the announce request is coming from a connected client. The connect request contains a magic constant (0x41727101980) which is 8 bytes, a 4 bytes action value (set to 0), and a 4 bytes transaction id (random number generated by the client). This makes the total request size 16 bytes. These numbers have to be in big-endian format. Upon receiving this request, the tracker responds with a 4 bytes action value (0), the 4 bytes transaction id that was sent by the client, and an 8 bytes connection id making it a total of 16 bytes for the size of the response payload. These numbers are also in big-endian format. The transaction id is verified by the client to ensure it’s equal to the one sent in the request, this ensures that the client is receiving its own response and not that of another client.

Here’s an example connect request message. The device is assumed to be a big-endian one. The parameters are shown here, including their hex equivalent. Note that each pair of hexadecimal values make one byte i.e a byte is between 00-FF.

magic_num = 0x41727101980 => 0000041727101980 (8 bytes)

action = 0 => 00000000 (4 bytes)

transaction_id = 765 => 000002FD (4 bytes)

// the hex values are concatenated

message = 000004172710198000000000000002FD (16 bytes)

Here’s a reply message from the tracker.

00000000000002FD00000003DCB35E1B (16 bytes)

//the decomposed components of the message and their translation will be

action = 00000000 (4 bytes) => 0

transaction_id = 000002FD (4 bytes) => 765

connection_id = 00000003DCB35E1B (8 bytes) => 16587644443

After verifying the transaction id, the client can initiate the announce cycle.

The announce cycle is where the client gets the list of peers from the tracker. The request includes the connection id sent by the tracker in the connect cycle, an action value (set to 1), a transaction id, and the parameters that are stated in the HTTP protocol. The compact parameter is not set since the udp protocol is a binary protocol anyway, so all peers list received is in binary format (akin to setting compact to 1). The response sent by the trackers includes the action value (set to 1), the transaction id sent by the client, and the values defined in the http protocol explanation above. Please note that all the numbers sent and received in this cycle are also in big-endian format.

Here’s an example announce request message. The device is assumed to be a big-endian one

connection_id = 16587644443 => 00000003DCB35E1B (8 bytes)

action = 1 => 00000001 (4 bytes)

transaction_id = 823 => 00000337 (4 bytes)

info_hash = 123456789ABCDEF123456789ABCDEF123456789A //already in hex (20 bytes)

peer_id = -BT0001-948911116432 => 2D4254303030312D393438393131313136343332 (20 bytes)

downloaded = 0 => 0000000000000000 (8 bytes)

left = 489033 => 0000000000077649 (8 bytes)

uploaded = 0 => 0000000000000000 (8 bytes)

event = 0 => 00000000 (4 bytes)

ip_address = 0 => 00000000 (4 bytes)

key = 0 => 00000000 (4 bytes)

num_want = -1 => FFFFFFFF (4 bytes)

port = 6889 => 1AE9 (2 bytes)

// the hex values are concatenated together

message = 00000003DCB35E1B0000000100000337123456789ABCDEF123456789ABCDEF123456789A2D4254303030312D393438393131313136343332000000000000000000000000000776490000000000000000000000000000000000000000FFFFFFFF1AE9 (98 bytes)

Here’s a reply message to the above request

000000010000033700000BAC000000010000000136405D2D4E2B4E642D3625C0 (32 bytes)

// the decomposed components and their translation will be

action = 00000001 (4 bytes) => 1

transaction_id = 00000337 (4 bytes) => 823

interval = 00000BAC (4 bytes) => 2988

leechers = 00000001 (4 bytes) => 1

seeders = 00000001 (4 bytes) => 1

first peer ip&port = 36405D2D4E2B (6 bytes) => 54.64.93.45:20011

second peer ip&port = 4E642D3625C0 (6 bytes) => 78.100.45.54:9664

You can use the memcpy function to read and write messages, like the above, in C. Python has the struct package. PHP has the pack and unpack functions for writing and reading messages respectively. Java has the ByteBuffer class. You can find equivalents in other languages too.

I recommend that you read more about the tracker UDP protocol.

After the client verifies that the transaction id received is equal to the one sent, the peer list can be parsed and connections to each peer are initiated using the peer message protocol.

Peers

Communication with other peers is done to each ip and port address received from the trackers via the TCP protocol. The protocol type for this is binary, so it has a similar format as the one in the tracker UDP protocol. Because your client connects to more than one peer, these connections have to be handled by your application. Some of the options to do that in C are:

The socket descriptor has to be set to non-blocking when using non-multithread methods. It’s very likely some peers might not immediately reject your connection, so connecting with timeouts is recommended to avoid delay. Doing this in C is not so straightforward, unlike Python. A way to do this is to use the select function.

Once two peers are connected, the first message type that is exchanged is the handshake message.

Handshake Message

Illustration of handshake message, from Jesse Li

This message type is required. The peer that initiated the connection has to send this message to the accepting peer. Once this message type is sent by the initiating peer, the accepting peer replies with its handshake message.

The structure of the message is <pstrlen><pstr><reserved><info_hash><peer_id>. <pstrlen> is always 19, it signifies the length of <pstr> which is always “BitTorrent protocol”. <reserved> is always 0 except if you want to support extensions to the protocol. <info_hash> is the same info hash that was sent to the tracker(s). <peer_id> is the same peer id that was also sent to the tracker(s). The length of this message is 68 bytes. Here’s an example.

pstr_len = 19 => 13 (1 byte)

pstr = BitTorrent protocol => 426974546F7272656E742070726F746F636F6C (19 bytes)

reserved = 0 => 0000000000000000 (8 bytes)

info_hash = 123456789ABCDEF123456789ABCDEF123456789A //already in hex (20 bytes)

peer_id = -BT0001-948911116432 => 2D4254303030312D393438393131313136343332 (20 bytes)

// The hex values are concatenated

message = 13426974546F7272656E742070726F746F636F6C0000000000000000123456789ABCDEF123456789ABCDEF123456789A2D4254303030312D393438393131313136343332 (68 bytes)

The only difference between the message sent and the message received should be the peer_id. All other values should be the same. The info_hash in the received message should be verified to avoid issues.

Note that the reply to the sent handshake message may also include additional messages like the bitfield/choke/have message type. You can read more details about the handshake message here.

Messages

This section covers the core of the BitTorrent protocol. The list of message types are the keep-alive, choke, unchoke, interested, uninterested, have, bitfield, request, piece, cancel and port messages. You can see details about them here.

The messages all begin with the message length (size = 4 bytes). All message types except for the keep-alive one also include the id (size = 1 byte), which identifies the type of message that is sent and received. The other parts of the message (for some message types) are specific to the message type.

There’s a possibility that a client might receive more than one message type in one segment. The message length value should be used to differentiate the message types when reading the segment. It is also possible that less than the entire message might appear in the segment. Your implementation should have a way of handling this. For example, you could use an internal buffer when reading from the socket.

Some of the more important message types are covered below:

Choke/Unchoke message

These message types are for notifying refusal or assent to serve file(s) pieces to another peer. A peer sends a choke message type to signal a refusal to serve file(s) pieces to the recipient. The structure of the message is

length = 1 => 00000001 (4 bytes)

id = 0 => 00 (1 byte)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 0000000100

Upon receiving this message, the receiver should refrain from requesting pieces from the sender until it receives an unchoke message type from the sender peer. The unchoke message gives the receiver license to request pieces from the sender. The structure of the message is:

length = 1 => 00000001 (4 bytes)

id = 1 => 01 (1 byte)

The hex values are concatenated together

message = 0000000101

A choke message type can be sent at any time, so your implementation needs to watch out for it. A choke message can also be sent alongside the handshake message by the accepting peer to prevent an immediate request from the initiating peer.

Interested/Uninterested message

These message types are for notifying refusal or assent to receive file pieces from another peer. An interested message type is sent to inform the receiver that the sender wants to receive file pieces from it. On receiving the message, the recipient could choose to send a choke message to prevent the sender from requesting file pieces from it. It could also send an unchoke message to a choked sender, based on the choking algorithm that the peer adopts. Note that the interested message doesn’t require a reply.

The structure of an interested message is

length = 1 => 00000001 (4 bytes)

id = 2 => 02 (1 byte)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 0000000102

The uninterested message is sent by a peer to another peer if the receiver doesn’t have the pieces the sender wants or the receiver’s upload speed is too low for the sender. The recipient could choose to choke the sender or ignore the message.

The structure of an uninterested message is

length = 1 => 00000001 (4 bytes)

id = 3 => 03 (1 byte)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 0000000103

Have/Bitfield message

A peer has to signal the pieces it has to another peer. It is frequently appended to the handshake message response. They are two message types that do this. Either one of them is sent or a combination of both is sent.

The have message type is sent by a peer to signal that it has a piece. A peer can send several of them to the other peer. For example, if a file contains 16 pieces and a peer has 14 of them, the peer could send 14 have messages to the other peer each containing a different piece index. A client must have a way to keep a record of pieces that each peer it’s connected to has.

An example of a have message is shown here

length = 5 => 00000005 (4 bytes)

id = 4 => 04 (1 byte)

piece_index = 10 => 0000000A (4 bytes)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 00000001040000000A

The piece_index is the index of the piece denoted in the message. It is zero-based (the first piece will be index 0).

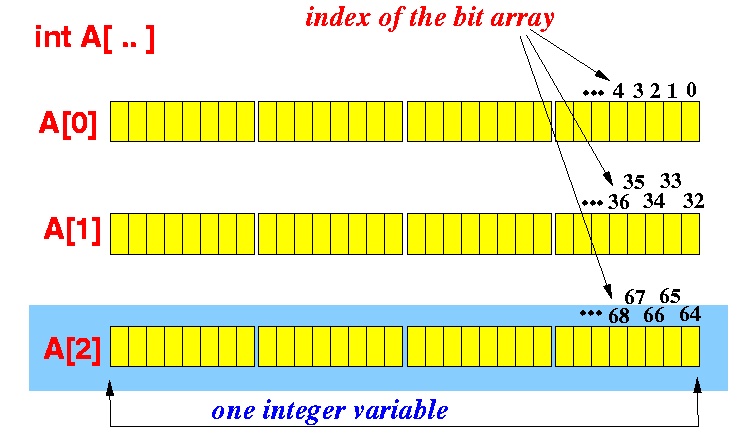

Structure of bit-array, from Emory U.

Another way that a peer can signal the pieces it has is to send them all as a bitfield message. A data structure that a peer can use to store the pieces it has is a bit-array, which is an array of bits. The array length is the number of the shared file(s) pieces. Each item in the array is 1 if the file piece is absent, or 0 if the file(s) piece is absent. Continuing the example above, the peer having 14 pieces might not have pieces 10 and 13, so the bit-array would be 1111111110110111. C has no native structure for bit-arrays, so an array of characters can be used where each character represents 8 pieces, meaning the array would have number of pieces/8 items. Note that this length is rounded up to the nearest integer, so the length for 16 file(s) pieces will be 2. Any spare bits at the end of the last character are set to 0.

An example of a bitfield message is shown below

length = 3 => 00000003 (4 bytes)

id = 5 => 05 (1 byte)

bitfield = 1111111110110111 => FFB7 (2 bytes)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 0000000105FFB7

A peer can send a bitfield or have message once it has downloaded a complete piece to all the connected peers if it wants to share files.

Request message

A peer sends a request message to download a piece from another peer. A file(s) piece is usually too large to download once, so it should be divided into sub-pieces or blocks. According to the spec, the recommended size of a block is 2^14 bytes (16 KB). If the piece is not evenly divisible by the block size, the last block would have a smaller size. A block should also have an offset attribute, which signifies its location within the piece.

When requesting a block from another peer, the peer must have the piece containing the block. The order of downloading a block is up to the client. It could be in order, random, or any fancy algorithm. During downloads, it is recommended that a check for outstanding downloads that take more than a set time is executed. These delayed blocks should be re-requested to speed up the entire process.

An example of a request message for a block in piece index 13 (zero-based) is shown below.

length = 13 => 0000000D (4 bytes)

id = 6 => 06 (1 byte)

index = 13 => 0000000D (4 bytes)

begin = 49152 => 0000C000 ( 4 bytes )

block_length = 16384 => 00004000 (4 bytes)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 0000000D060000000D0000C00000004000

The index is the index of the piece that contains the block. The begin value signifies the offset in bytes that the requested block is located within the file(s) piece. In the example above, the block starts from the 49152nd byte, which makes it the 4th block in the file(s) piece. The block_length is the size of the block requested in bytes.

Piece message

This message is a response to the request message. It contains the block data whose length is equal to the length value requested.

The structure of the piece message for a block in piece index 13 (zero-based) is shown

length = 9 => 00000009 (4 bytes)

id = 7 => 07 (1 byte)

index = 13 => 0000000D (4 bytes)

begin = 49152 => 0000C000 ( 4 bytes )

block = ADB40212..... (16384 bytes)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 00000009070000000D0000C000ADB40212.....

The index is the index of the piece that contains the block. The begin value is the offset in bytes where the requested block is located within the piece. In the example, the block starts from the 49152nd byte. The block is the block data itself, which the example shows in truncated form. The block data in the example above is 16KiB in size.

When all the blocks of a piece have been downloaded and merged, a hash of the piece should be checked against the piece hash contained within the pieces element of the info dictionary of the torrent metafile. If the hash does not match, the piece should be discarded and its blocks should be requested again.

Cancel/Port message

A peer sends the cancel message type if it executes the End Game algorithm. The message is sent as a form of politeness and to save bandwidth. I didn’t implement the algorithm, so there’s no need for my client to send the cancel message.

The structure of the message is similar to that of the request message.

length = 13 => 0000000D (4 bytes)

id = 8 => 08 (1 byte)

index = 13 => 0000000D (4 bytes)

begin = 49152 => 0000C000 ( 4 bytes )

block_length = 16384 => 00004000 (4 bytes)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 0000000D080000000D0000C00000004000

The only difference between the cancel message and the request message is the id i.e. 8 for the cancel message type against 6 for the request message.

The port message is needed by clients that implement a DHT tracker. Like the cancel message, I didn’t implement DHT, so there’s no need for my client to send the port message.

It is sent to the receivers to notify them of the port the sender DHT’s node is listening on. The structure of the message is shown here

length = 3 => 00000003 (4 bytes)

id = 9 => 09 (1 byte)

port = 48879 => BEEF (2 bytes)

The hex values concatenated together

message = 0000000109BEEF

Writing a File

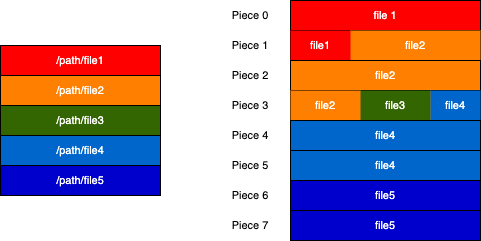

Illustration showing the relationship between files and pieces. Multiple files can share a piece, and multiple pieces can belong to a file. This relationship is represented via colors in the diagram above.

When a piece is verified, it is still in the RAM. Keeping all the file(s) pieces in memory can use lots of memory. For example, a 4GB file would use up to ~4GB of memory if all its pieces are kept there. It is recommended that once a piece is verified, it should be written to the file except if the peer is currently sharing that piece.

If the torrent contains only one file, writing a piece to the file is a trivial matter of using the piece index to calculate the offset within the file and writing the piece from that offset. A lot of programming languages provide the mechanism for that.

In the case of a torrent containing more than one file, it can be tricky. It is tricky because a piece might belong to more than one file or a file might contain more than one piece. If all the pieces are merged, they will be written to the files according to how the file names are arranged in the files list of the info dictionary. The length element of each file should be used as a guide on how much data has to be written to that file.

Your piece structure implementation should account for the files that each piece is written to along with the offset and length within each file.

Resources

- The official and unofficial specifications are a must-read.

- Some of the BEPs found on this page should also be read depending on your goals.

- Parts one and two of Kristen Widman’s article on writing a BitTorrent client are great to read too.

- You can find my implementation in C on Github.

Happy coding!

Thanks to Nwamaka Imasogie and Lekan Raheem for reading drafts of this.